We all begin our lives in much the same way. As infants, we were subject to a simple summary of forces: gravity, our body weight, and whatever we could hold in our hands. We spent most of our time rolling on the floor, crawling from room to room, and trying to figure out how to stand. Amazingly, we have observed that the natural movement of babies and toddlers is surprisingly efficient. Although balance proves mysterious, the squat, gait, bend and reach mechanics express themselves cleanly. Soon, however, children are expected to sit in school and learn, and so begins the steady decline of posture in our bodies. As we get older, we end up sitting in high schools and universities for a long time, absently drifting towards a compromised shoulder, hip, and spine position. When we finally do rise, it is to the symphony of dull aches in our lower back, knees, shoulders, or feet. Then we continue on our busy way, sitting on buses or in cars driving to our next seated destination. A desk office or the kitchen table provides the next destination for our “weary bones,” flattened by an exhausting day of sitting. It may seem dramatic, yet an estimated 80% of all adults experience lower back pain; the destructive nature of desk posture and inactivity contributing to the lion share of this statistic (National Academy of Sports Medicine: Corrective Exercise Specialization, First Edition Revised, page 3). More often than not, and understandably so, our hard-working office employees and university students feel so afflicted by the energy-draining effect of poor posture and inactivity, that choosing to exercise becomes even more challenging than average. When they finally enter our training facilities, their movement patterns have been so affected by the “cumulative injury cycle” that exercise increases their pain and discomfort, the complete opposite of our objective.

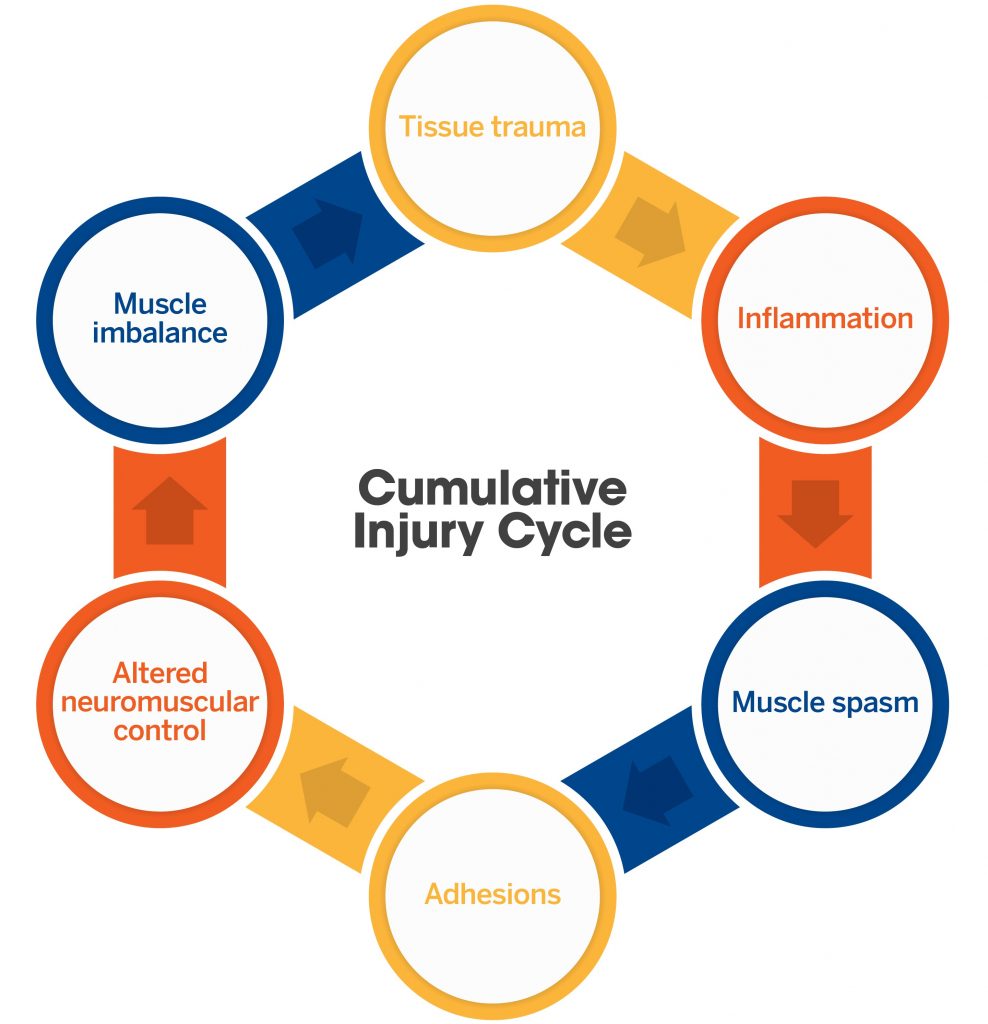

The Cumulative Injury Cycle

Generally speaking, poor posture and repetitive movements create dysfunctional connective tissue. When dysfunctional connective tissue is present, our bodies treat the dysfunctional tissue as an injury and initiates a process known to the National Academy of Sports Medicine as “the cumulative injury cycle.” Trauma to the muscles and fascia creates an inflammatory response leading to a protective response from the body. This mechanism increases muscle tension and causes muscle spasms. Not the type of muscle spasms that wake us up screaming in the middle of the night, clutching our calves. Instead, these are micro spasms that create adhesions, or Trigger Points, across muscle fibers. These adhesions change how our body recruits muscles, resulting in what we call “altered neuromuscular control.” Altered neuromuscular control leads to poor posture and repetitive movements responsible for dysfunctional connective tissue, and so, the cycle repeats.

For example, if a desk worker’s pecs become tight due to their hunched posture, the body treats this tight tissue as “injured,” and inflammation increases. When they exercise in the evening, they may experience a lot of tricep or deltoid tension when performing a chest press. This “synergistic dominance” happens due to the body’s protective response to the “trauma” of desk posture. So now we develop poor, loaded movement patterns that create even more tissue trauma, and, eventually, injury. Suppose our desk worker took a few minutes to use Trigger Point Therapy at the beginning of their workout. In that case, they could have reduced the body’s protective response to inflammation and restored neuromuscular control enough to use the right muscles and provide a break in the “cumulative injury cycle.” Using Trigger Point Therapy to break the “cumulative injury cycle” is one step of four required to reverse poor length-tension relationships and restore neuromuscular control.

Foam Rolling: The Science

Despite the responsibilities placed on society’s desk jockeys’ weary shoulders, Foam Rolling lends its benefits to those with stiff muscles, sore joints, poor posture, or even those chasing performance objectives. Using a Foam Rolling tool over stiff connective tissue, tiny receptors within the muscle belly feed the central nervous system information. In turn, the central nervous system releases the residual muscle tension or muscle tone (which could manifest in the form of a pump from a workout, or from holding a posture for a long time). This central nervous response allows the muscles to lengthen or relax passively. Although you may be targeting a single muscle group, the autonomic nervous system applies a domino effect to the rest of the muscles by changing fluid dynamics so that blood can flow through the body more effectively. In this way, Foam Rolling becomes a great targeted AND global relaxation technique. Consequently, tight connective tissue (that knot you feel in your back or legs) generally indicates a region of reduced blood flow. Our bodies give us a pain response when we drive over the top of a “fascial adhesion” or a muscle knot, thus indicating a region that could benefit from targeted therapy.

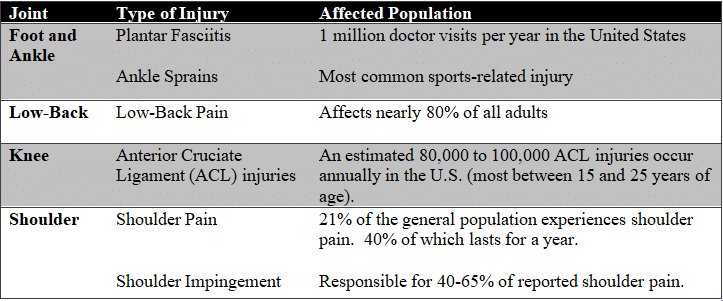

Frequently, circulation issues present throughout the office employee’s career or the university student’s degree due to their environment’s seated nature. Blood flow is inhibited throughout the entire body, increasing the chances of developing varicose veins, blood pooling, and numbness and tingling through the fingers and toes. Unfortunately, the list of risks goes beyond general discomfort. These altered length-tension relationships and poor neuromuscular control dramatically increase performance risks. Here is a list highlighting the most common injuries for both the general population and athletes.

Trigger Point Therapy Techniques

There are two Trigger Point Therapy techniques that we can use: the “oscillation” technique and the “pin and move” approach. We can use our “oscillation” technique to manually stimulate the underactive muscle fibers of a muscle group. Using “pin and move,” we can locate a “fascial adhesion,” trap it under a Foam Roller or other type of Trigger Point tool and mobilize the joint to deactivate overactive tissue. We will use this technique on overactive muscles.

Check out the video below for a quick tutorial of the two techniques:

Try out these techniques before your next workout so you can feel the difference. As always, to keep up with the latest BCPTI has to offer, follow us on Instagram @bcpti, and subscribe to our newsletter!

Tags:

Related Posts

We’re here to help you!

Questions, comments or want to register? Fill out the form below and we will contact you shortly. Thanks!

"*" indicates required fields